Revisiting Barcelona’s bright, brief Art Nouveau heyday

Modernisme Català

-

Barcelona’s Casa Lleó Morera first floor gallery with stained glass by Antoni Rigalt, ca. 1911

<em>© Wikimedia Commons</em>

-

Bench for Casa Calvet by Gaudí

<em>© Museu del Modernisme Català (MMCAT)</em>

-

Chair for Casa Calvet by Gaudí

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Bench for Casa Batlló by Gaudí

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Coat hook for Casa Calvet by Gaudí

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Stool for Casa Calvet by Gaudí

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Mirror for Casa Calvet by Gaudí

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Hall bench by Joan Busquets

<em>© MMCAT</em>

-

Cabinet by Gaspar Homar

-

Chairs by Gaspar Homar

-

Sketch by Joan Busquets

<em>© MNAC</em>

-

Sketch for Casa Lleó Morera by Gaspar Homar

<em>© Museo Nacional d'Art de Catalunya (MNAC)</em>

It flourished with unprecedented exuberance, lasted only a short time, and then quickly faded away: Modernisme Català was the Barcelona-centered offshoot of the Art Nouveau spirit that swept Europe toward the end of the 19th century. Like all regional manifestations of this aesthetic crusade, Modernisme found expression in a wide range of art forms—architecture, interiors, furnishings, décor, painting, sculpture, illustration, fashion, even literature—and the style’s highly inventive formal repertoire drew inspiration from the most progressive intellectual and social developments of the day.

Throughout Europe, cities grew and the middle class expanded, bringing a taste for smaller interiors in which comfort, leisure, and intimacy were paramount. As populations fled the countryside for urban opportunities, a cult grew up around the veneration of nature. Modernisme spoke to these marks of modernity through an eclectic proliferation of designs enlivened by hyper-fluid lines and biomorphic forms, often set in asymmetrical compositions and always permeated with a dynamic sense of movement.

The birth of Modernisme Català is often traced to the Universal Exposition of 1888, which was hosted by the city of Barcelona. Although this world’s fair was considered a commercial failure and many of the style’s most floral expressions did not arise until later, from a local perspective, the event brought an influx of ideas and energy, encouraging synergies between tradition and innovation, craftsmanship and industry, at a time when Catalonians were seeking to define their cultural identity as distinct from other Spanish and European peoples.

The wealthy and artistic citizens of Barcelona at the time grew increasingly cosmopolitan through close ties with Paris, where Art Nouveau was taking root. Barcelona’s vanguard urbanites fully embraced the movement and rapidly adopted and adapted its architecture, decorative arts, graphic design, and fashion in an attempt to achieve the au courant total look—though instilled with a local flavor all their own. The magazine L’Avenç documented the latest Modernisme expressions, and many of its proponents convened at the café Els Quatre Gats (which still operates in Barcelona today) to nurture the Catalonian interpretation of the new art forms in vogue throughout the rest of Europe.

Ebonist and editor Francesc Vidal was the first in Barcelona to launch a business devoted to Modernisme décor. In the 1880s, he opened a workshop called Industrias de Arte, which was dedicated to producing all types of handmade luxury objects—furniture, glass, porcelain, and more—for the homes of the Barcelona bourgeoisie. Vidal sought to modernize craftsmanship and encouraged his network of woodworkers, metal smiths, glassmakers, and ceramists to experiment following the ideals of the English Arts and Crafts movement. Nearly every decorative artist of the Modernisme style worked with Vidal at one time or another.

Vidal produced the furniture designs for Palacio Güell (1886-88), the first large scale commission received by Antoni Gaudí—certainly the most well known proponent of the style. As the 20th century approached, Gaudí evolved his architecture and interiors toward ever greater experimentation and fluidity. His truly original furniture designs for the Casas Calvet (1900-01) and Batlló (1907) are wonderful exemplars of the way the era’s artists integrated the Modernisme style across scales and media to dramatic yet harmonious effect. For the Casa Calvet, Gaudí designed a suite of furniture, which included benches, chairs, armchairs, stools, and mirrors. Made in oak, these pieces are sculptural, curvaceous, and asymmetrical, enriched with decorative motifs that are both restrained and organic, and which highlight the honesty of the construction. The Casa Batlló’s interior included simple but voluptuously shaped tables, chairs, and benches in ash designed by Gaudí with another master of Modernisme, Josep Maria Jujol.

Gaudí’s architectural commissions often included striking installations of stained glass, which became a popular and lavish medium for Modernisme homes at the turn of the 20th century. Vidal, of course, was at the epicenter of stained glass production in Barcelona, thanks to the work of his son Frederic who had studied the cloisonné technique in England. It was another firm, however—Rigalt, Granell y Cia—which would ultimately produce the best examples of the style’s elaborate glasswork, as in the landmark Palau de la Müsica (1905-08), designed by architect Lluís Domènech I Montaner.

Production of the elongated, asymmetrical shapes of Modernisme furniture required highly skilled craftsmanship, best exemplified in the work of two legends: Gaspar Homar and Joan Busquets. Homar apprenticed in cabinetmaking in Vidal’s workshop, and became particularly adept at producing floral decoration on woods with complex grains. One of Homar’s most striking works is the interiors of Casa Lleó Morera by Doménech i Montaner. Homar employed a great deal of intricate wood marquetry and metal detailing—a technique with a long tradition in Catalonia. His naturalistic flowers and stylized female figures are reminiscent of those of the Nancy school in France, a major center of Art Nouveau production. His work in this field is outstanding, especially the chromatic range he achieved by using a variety of woods in a spectrum of shades.

Joan Busquets, meanwhile, worked in his family business, which supplied furniture, glass, and metalwork to a roster of wealthy clients. He had a fondness for curvaceous furniture forms, but was rather controlled with sumptuous embellishments, like marquetry. Instead he preferred stained pyro-engravings—burnt-in illustrations of birds and flowers that tended toward a style reminiscent of the more geometrically inclined Viennese Secession.

Another area where the movement made an impact was in jewelry, in particular through the work of Luis Masriera, who was a true devotee of the trends coming from Paris at the time. Masriera worked in his family business from a very young age and went abroad to study the art of Limoges enamels. During his trips, he became an admirer of the great René Lalique, and when he returned to Barcelona, he began to design beautiful pieces inspired by nature: butterflies, birds, flowers, and female busts and figures. He primarily used his own perfected technique of translucent enamels, obtained by submerging opaque glass in acid. The extraordinary quality of his execution has made Masriera’s work the focus of many collectors through to the present day.

There is no clear-cut date for Modernisme Català’s demise, but by the 1920s the style’s rich ornamentation and eclecticism had given way to the more subdued and rational approach of the modernism movement, which was just beginning to formalize across Europe. As the parable goes, the candle that burns twice as bright burns half as long, and while the dazzling, creative flame of Modernisme may, in retrospect, seem to have been extinguished too soon, the flashes of its light are still gloriously evident around the beautiful city of Barcelona. And, only very occasionally, rare specimens of this opulent era in European design appear on the market.

Art and design from the era of Catalan Modernism is on display at the Museum of Caterlan Modernism (MMCAT) and the National Museum of Catalan Art (MNAC) in Barcelona.

-

Text by

-

Ana Domínguez Siemens

Ana is an award-winning, Madrid-based design writer and curator who regularly contributes both to exhibition catalogues and publications such as AD España, Vogue España, Diseño Interior, and DAMn°.

-

Découvrez plus de produits

Lampe de Bureau Vintage Art Nouveau Peinte, France

Portemanteau Art Nouveau avec Verre Tiffany, 1910s

Table de Salle à Manger Extensible Art Déco, 1910s

Table de Chevet Art Nouveau Vintage avec Dessus en Marbre, Allemagne

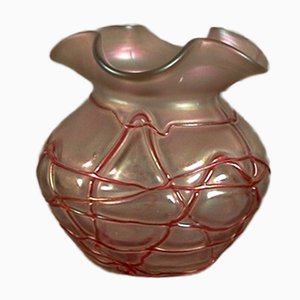

Vase Art Nouveau Vintage en Verre de Palme König, Allemagne

Table Fleur Vintage Art Nouveau en Chêne

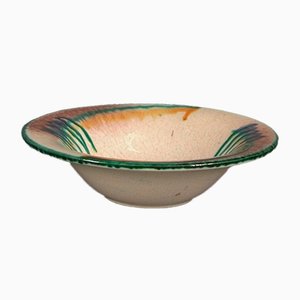

Bol Art Nouveau en Céramique, Allemagne, 1920s

Lustre Art Nouveau de Daum, Lorraine, France

Porte-Serviettes Art Déco en Bois Courbé de Thonet, 1910

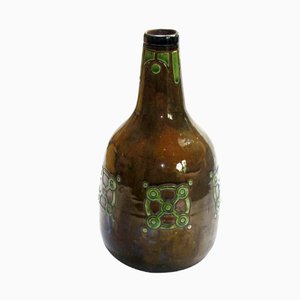

Grand Vase Art Nouveau de l'École des Arts et Métiers de Vienne

Jardinière Style Viennois Art Nouveau Antique en Argent

Table d'Appoint Vintage Art Nouveau en Fonte et en Laiton, France

Placard Vertiko Art Nouveau en Bois Souple avec Ornements Floraux, 1900s

Fauteuil Antique Art Nouveau en Bois avec Ornements

Support à Pot de Fleurs Art Nouveau Noir, 1910s

Desserte Vintage Art Nouveau avec Carreaux à Fleurs

Tabouret de Piano Art Nouveau Antique en Bois et Cuir

Tabouret Art Nouveau de Piano Pivotant Antique

Grand Plafonnier Viennois Art Nouveau, 1910s

Armoire Art Nouveau par Bergasse Lechantre, France

Lampe à Suspension Antique Art Nouveau, France

Vase Vintage Art Nouveau en Céramique de Karlsruher Majolika

Grand Vase Vintage Art Nouveau en Céramique, France

Plafonnier Art Nouveau, Autriche

Paravent Art Nouveau en Verre & en Bois, Autriche

Plafonnier Art Nouveau Porcelaine, 1900s

Table Art Nouveau de Kohn, 1900

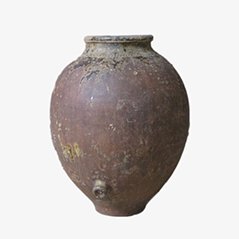

Jarre Antique en Argile, Espagne, 19ème Siècle

Lampe de Bureau Art Nouveau, France

Plafonnier Art Nouveau, France, 1900s

Lampe Art Nouveau, France, 1900s

Lustre PET Lamp par Alvaro Catalán de Ocón

Boîte à Biscuits Art Nouveau Antique en Céramique

Fauteuil à Oreilles Floral Art Nouveau, 1900

Grande Lampe Art Nouveau Viennoise, 1965

Tapis Art Nouveau Noué à la Main avec Motif Floral

Lampe de Bureau Art Nouveau en Forme de Fleur, France

Chaises de Salon Art Nouveau en Noyer, Set de 4

Lampe à Suspension Ajustable Art Nouveau en Laiton

Table d'Appoint Art Nouveau en Métal Forgé

Vases Art Nouveau de Royal Limoges, Set de 2

Affiche Publicitaire de Savon Providol Art Nouveau par C. Behrens pour Trumpf, 1909

Fauteuil Art Nouveau en Chêne Sculpté, France

Boîte aux Lettres Art Nouveau en Métal

Lampe de Bibliothèque Art Nouveau en Cuivre Plaqué de LUX

Publicité Art Nouveau en Carton pour JOB Cigarettes par Jules Cheret, 1889

Publicité Art Nouveau en Carton par Daniel Hernandez, 1889

Fauteuil Art Nouveau Vintage en Cuir

The Universal Exposition of 1888

© Diari Oficial N.63 / Wikimedia Commons

The Universal Exposition of 1888

© Diari Oficial N.63 / Wikimedia Commons

Glasswork inside Palau de Müsica

© Patrick Landmann / Getty images

Glasswork inside Palau de Müsica

© Patrick Landmann / Getty images